The big picture: It’s a common scenario – you leave the house without an umbrella only for the rain to catch you off guard. Instinctively, many of us hunch over and rush to shelter, assuming that speed will help keep us drier. But is this instinct correct? A physicist has now dissected the situation.

Jacques Treiner, a theoretical physicist from Université Paris Cité, has explored how walking speed affects the amount of rainwater a person encounters. His insights might prompt you to change your approach.

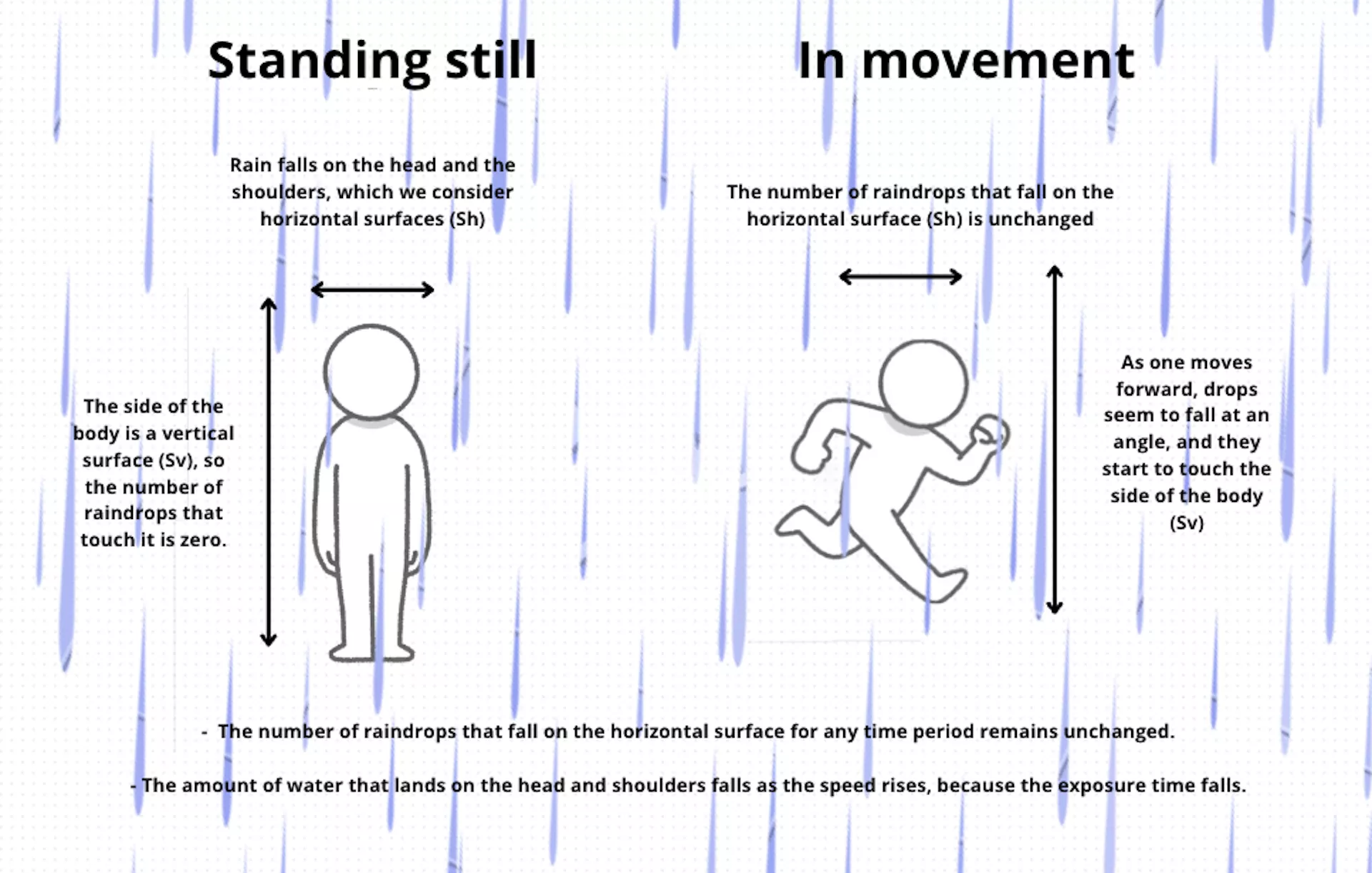

Treiner’s analysis starts by dividing the human body into two surface areas – vertical areas like your front and back, and horizontal areas like your head and shoulders. When you’re stationary in rain, only the horizontal surfaces get wet from drops falling directly from above.

However, once you start moving forward, the scenario changes. Due to your forward motion, from your perspective, the rain seems to fall at an angle. This angled path causes raindrops that would have landed ahead of you to instead strike your front surface.

The faster you advance, the more angled and horizontal the rain’s trajectory becomes, increasing the number of drops pelting your vertical surfaces with each step. While this might suggest a reason to slow down, it’s not that straightforward.

Although more raindrops may hit your front, the crucial point is that you spend less time in the rain by reaching shelter faster. These two effects cancel out – more drops per second at higher speeds, yet less overall time in the rain.

For the horizontal surfaces, like the head and shoulders, the situation is different. Treiner’s calculations suggest that irrespective of walking speed, the total number of drops hitting these areas remains constant. Raindrops from above fall at the same rate.

Yet, by moving faster and minimizing your exposure to the rain, you ultimately encounter less total water on the horizontal surfaces.

Treiner’s mathematical model concludes that the water touching your vertical surfaces stays constant regardless of your pace. However, the rain soaking your head and shoulders decreases as your speed increases.

Other factors come into play, such as wind, which could cause rain to fall at an angle, wetting you even if standing still. Or if caught in prolonged rain, water might start dripping from the horizontal areas, soaking you all over – regardless of walking speed. Considering these would complicate the formula further.

In light rain with minimal wind, Treiner’s advice is to “lean forward and move quickly when caught in the rain.” Just avoid leaning excessively, as an increased head surface might counteract the speed advantage.

To delve into the mathematics, you can read Treiner’s complete analysis on The Conversation.

Masthead credit: Mette Køstner