Certainly, let’s rewrite the provided content while keeping the HTML tags and image links intact:

The GeForce RTX 5080 seems more like an RTX 5070, given its hardware setup. This essentially explains why the RTX 5080 doesn’t quite excite – it’s positioned in what should be the 70 class tier, ideally priced lower, and offering notable improvements from its predecessors. Instead, Nvidia seems to be reaching for greater profit, which is what we delve into in this article.

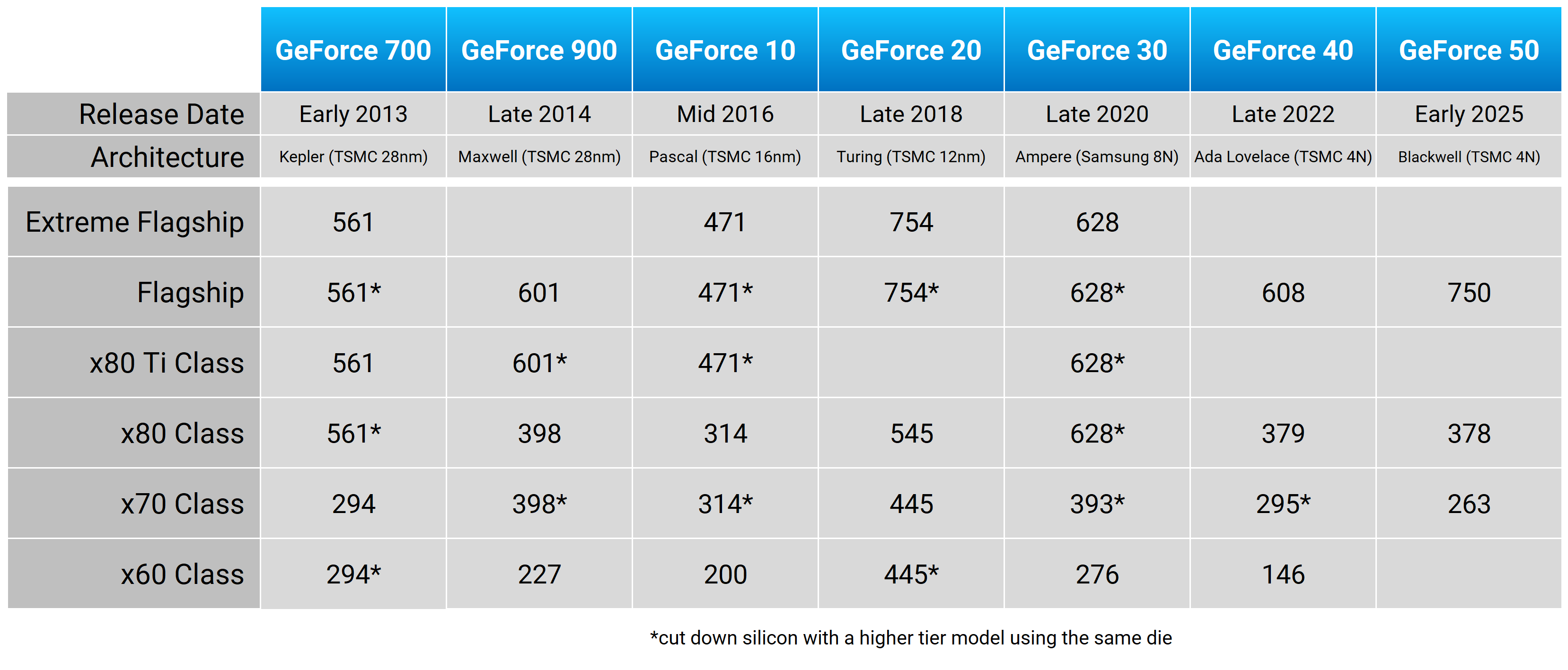

Our certainty about the RTX 5080 being essentially an RTX 5070 stems from a recent study where we mapped out Nvidia’s GPU configurations history, dating back to the GeForce 700 series from 2013 (see our feature: Nvidia’s GPU Classes Through the Years).

By evaluating the hardware setups in each class and comparing them against the flagship from different eras, we managed to create a “typical” Nvidia GPU generation that encapsulates the trends observed across six generations.

With the knowledge of what constitutes the hardware of both the RTX 5080 and the RTX 5090, we can fit them into the existing comparison to see how Nvidia’s freshly released generation adds up.

Spoiler alert: it doesn’t measure up well.

Analyzing GPU Core Configurations

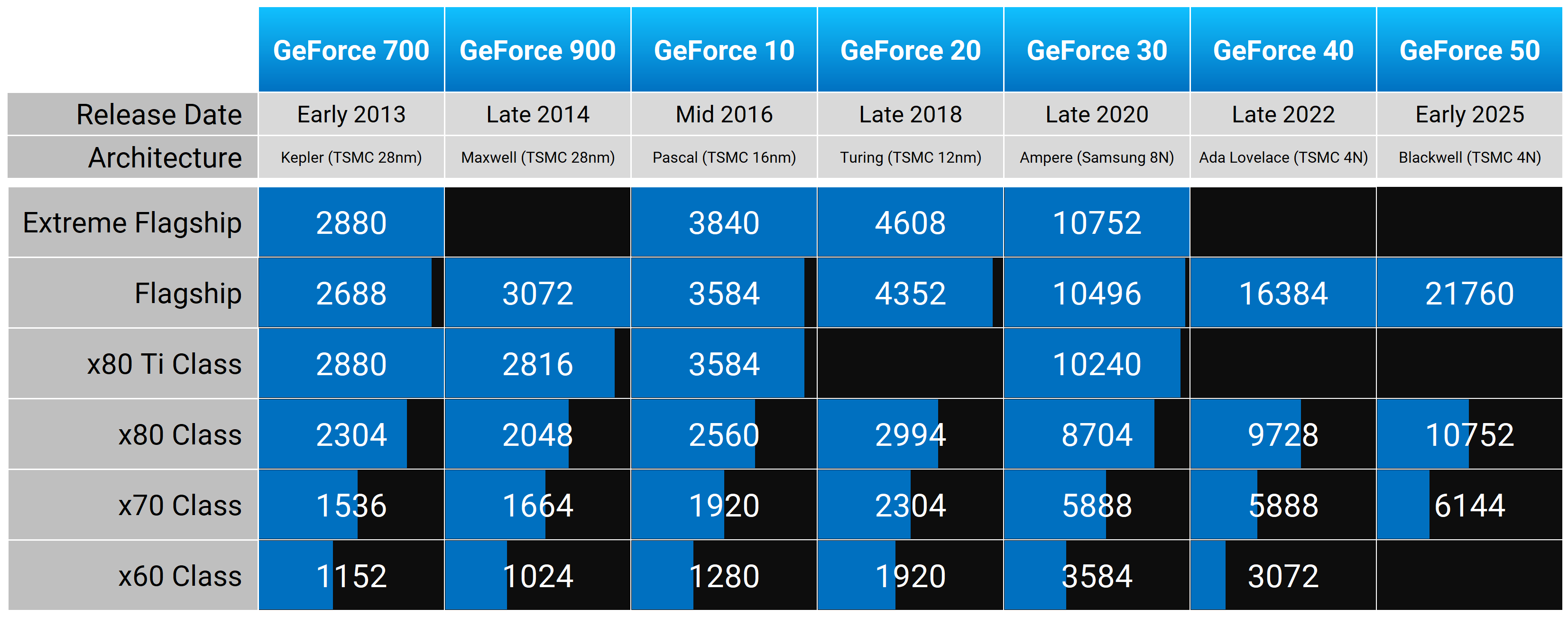

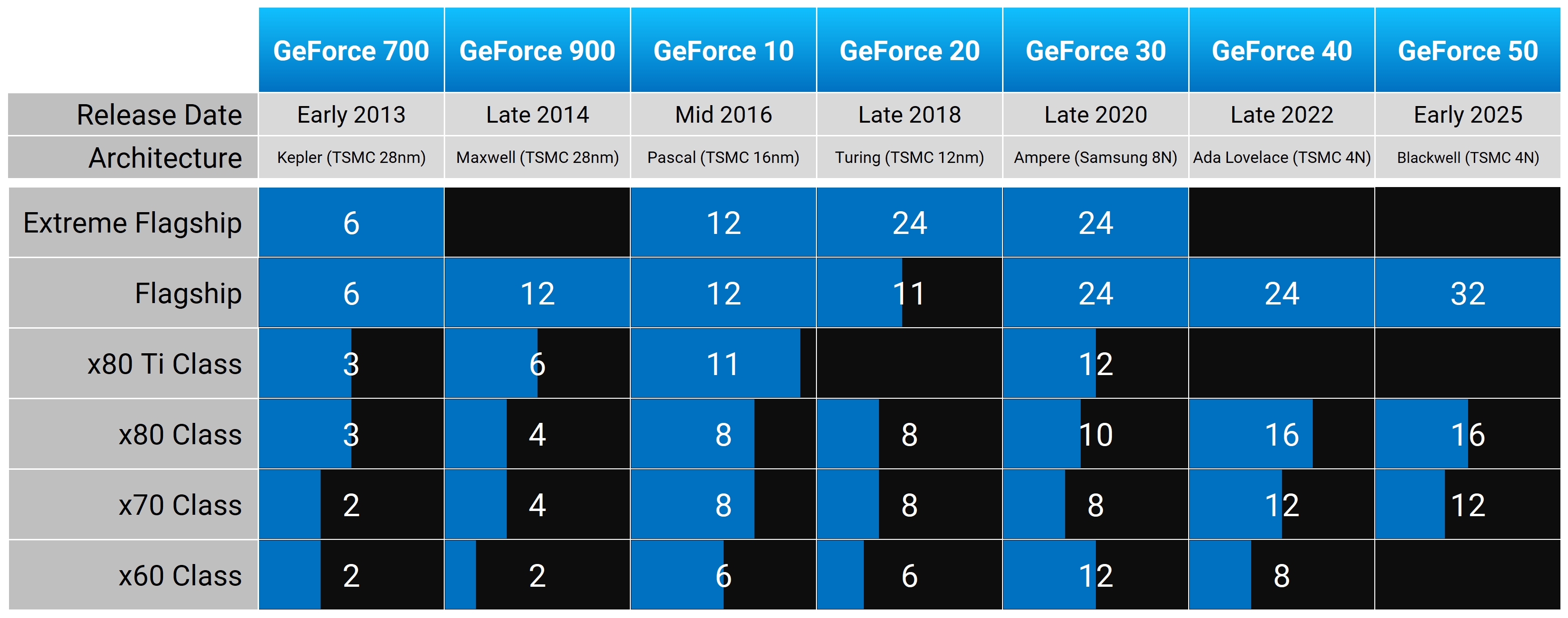

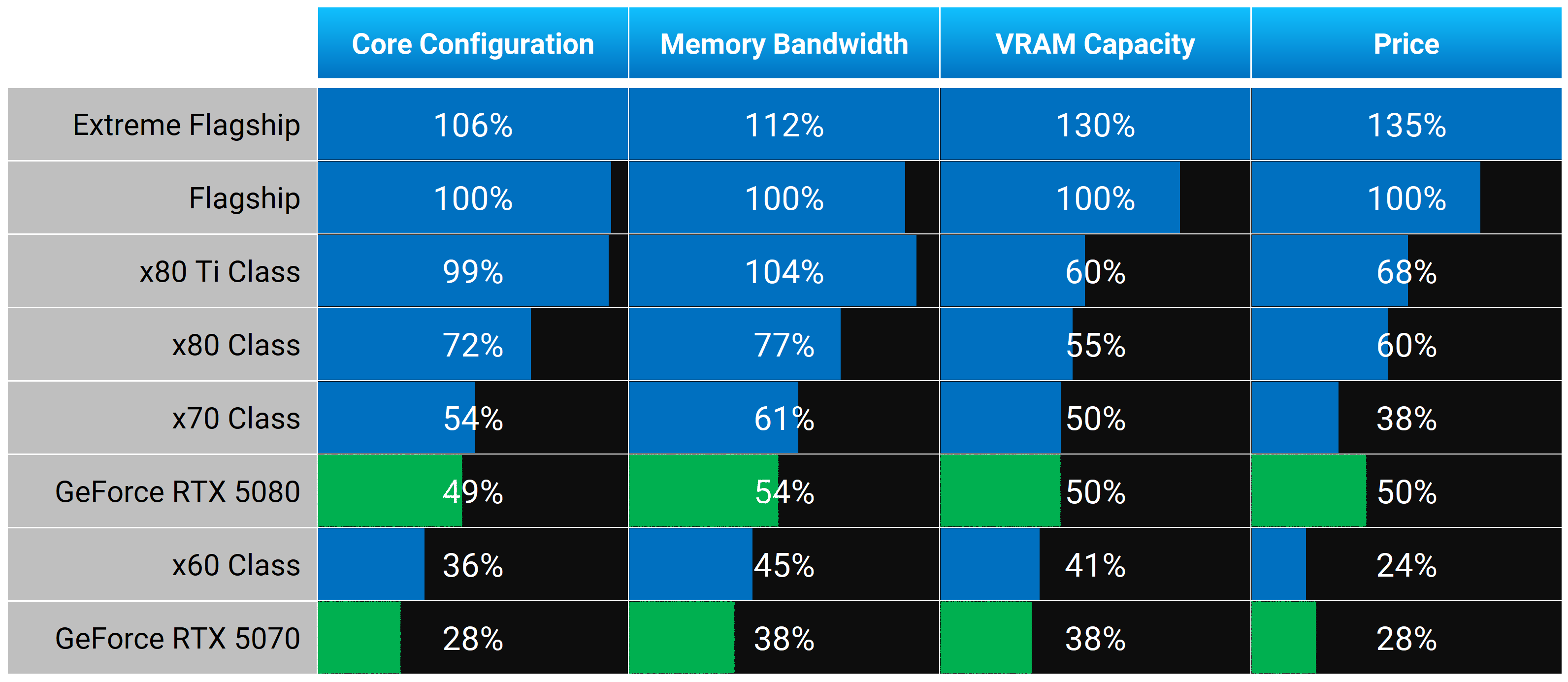

Looking at core configurations, the RTX 5090 is impressively outfitted with 21,760 CUDA cores. In contrast, the RTX 5080 pares it down to merely 10,752 CUDA cores, with the RTX 5070 reducing further to 6,144 CUDA cores. Essentially, the RTX 5080 encompasses only 49% of the flagship’s cores, and the 5070 just 28%.

Nvidia GPUs: Shader (CUDA) Core Count

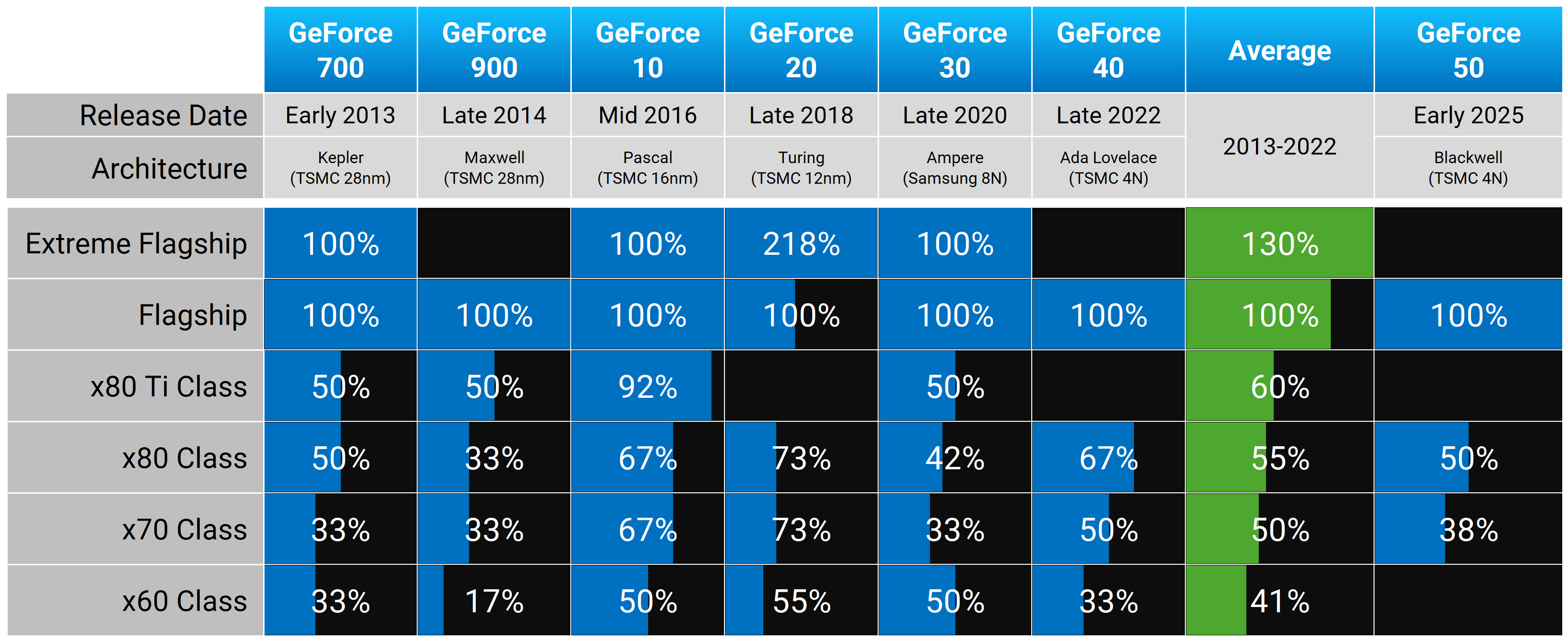

Historically, this is a rather lackluster hardware setup, even for the RTX 5080. Examining the previous six generations, the average 80-class GPU comprised 72% of the flagship’s cores. In some of the stronger generations like the RTX 30 series and RTX 3080, this number exceeded 80%. The 40 series was notably weaker at 59%, but the RTX 5080 is even less at just 49%.

When we position it against past 70-class GPUs over six generations, the RTX 5080 is below all, except for the RTX 4070. While it’s not as heavily pared down as the RTX 4070, the typical core count for a 70-class GPU over the six-year average is 54% of the flagship’s like for like comparison.

With the 5080 tallying up to merely 49%, it veers into the realm of a 60 Ti-type product. It wouldn’t have seemed outlandish to categorize it as a 60 Ti in the 30 series, there where the RTX 3060 Ti accounted for 46% of the flagship’s ( RTX 3090) core count, making it ostensibly reside between a 60 Ti and 70-class product.

Assessing VRAM

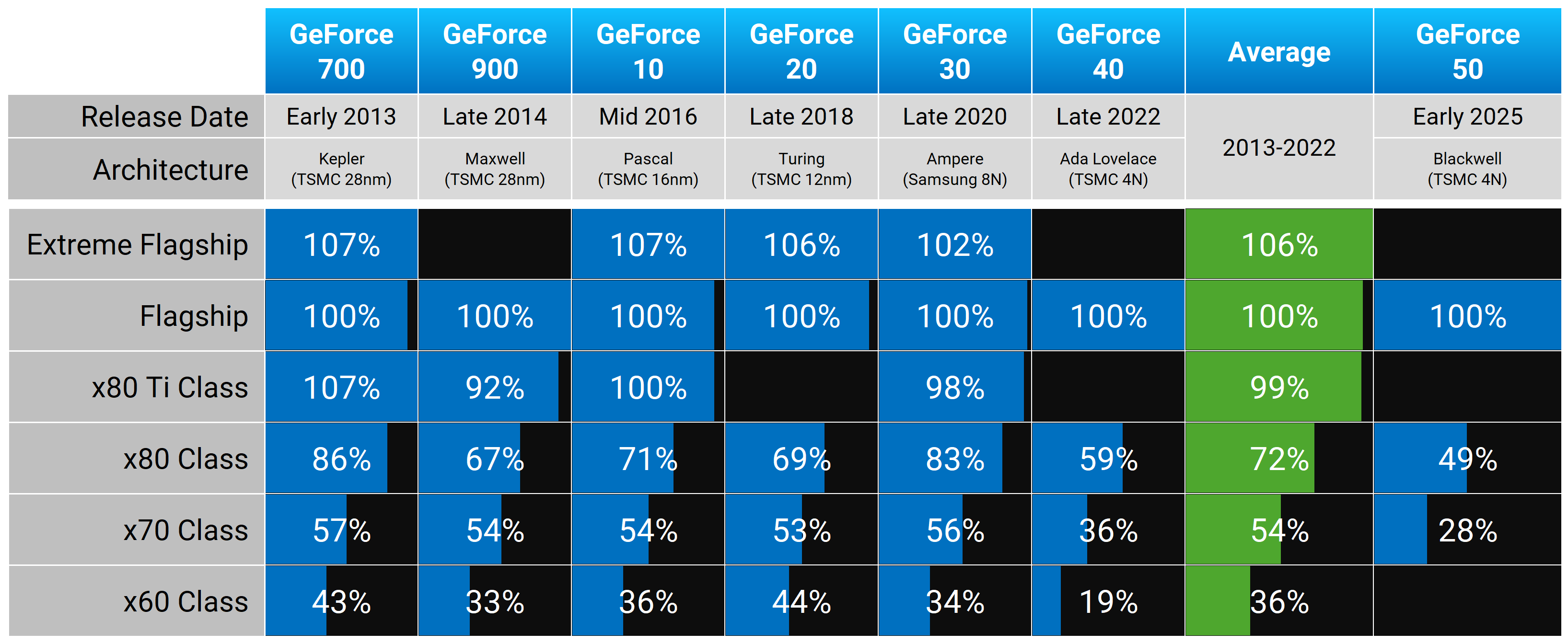

VRAM capacity too doesn’t stand impressively when under assessment. The RTX 5080 observes the most significant curtailment in memory bandwidth vis-à-vis the flagship in the 80-class so far.

While the 5090 is furnished with 1,792 GB/s of bandwidth, the 5080 manages just 960 GB/s, amounting to only 54% of its sibling’s bandwidth. Historically, this lands below the 70-class average, albeit three generations depict cutting closely to Blackwell’s reductions.

Nvidia GPUs: Memory Bandwidth (GB/s)

The RTX 5070 is likewise being carved into a sub-60-class configuration, although certain generations witness alignment with the 60-class threshold.

VRAM sizing varies widely across generations, and there have been notable fluctuations through the years. Yet, disappointingly, the RTX 5080 doesn’t outperform in this regard either, owning merely half the VRAM of the flagship. Typically, this embodies a 70-class characteristic, although the 80-class isn’t always stacked significantly higher in VRAM over its 70-class counterpart.

The RTX 5070, armed with 12GB of VRAM, mirrors more of a 60-series archetype, upholding what our discourse identifies as the minimum suitability for a $550 GPU in terms of VRAM volume.

Nvidia GPUs: VRAM Capacity (GB)

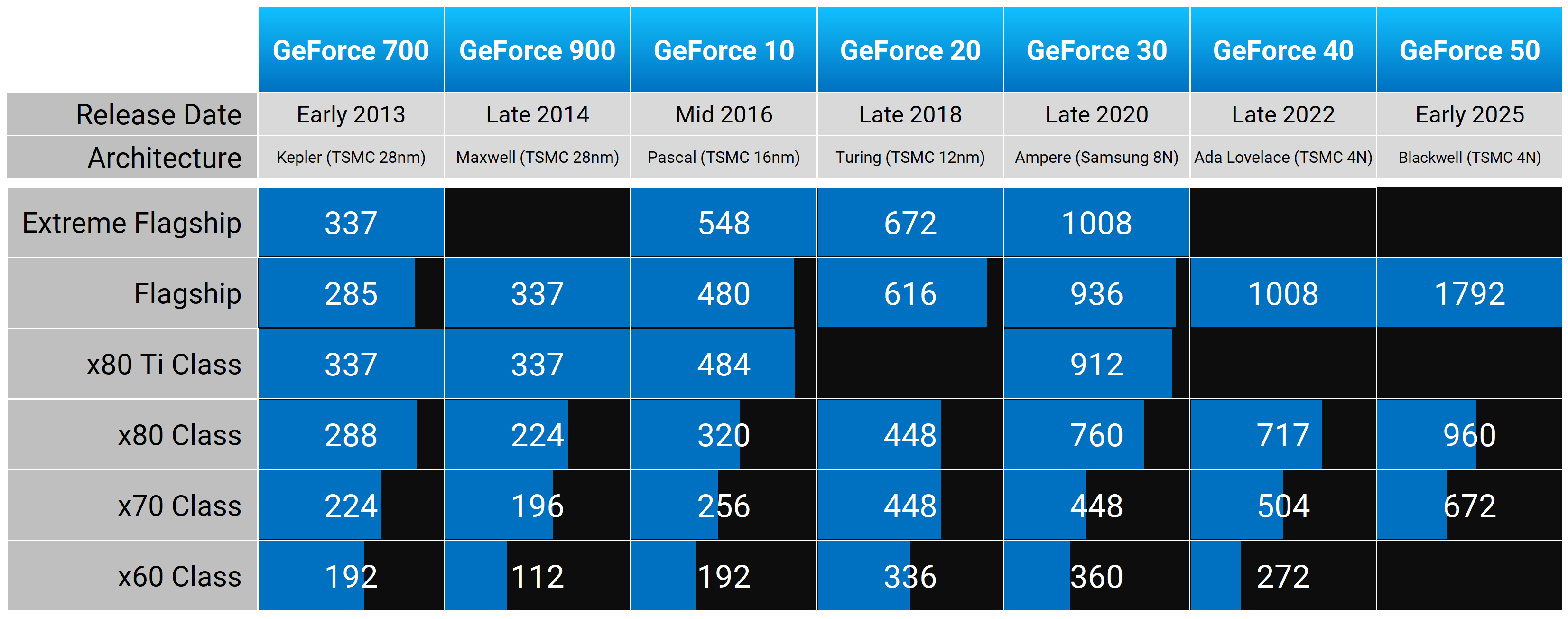

Evaluating GPU Prices

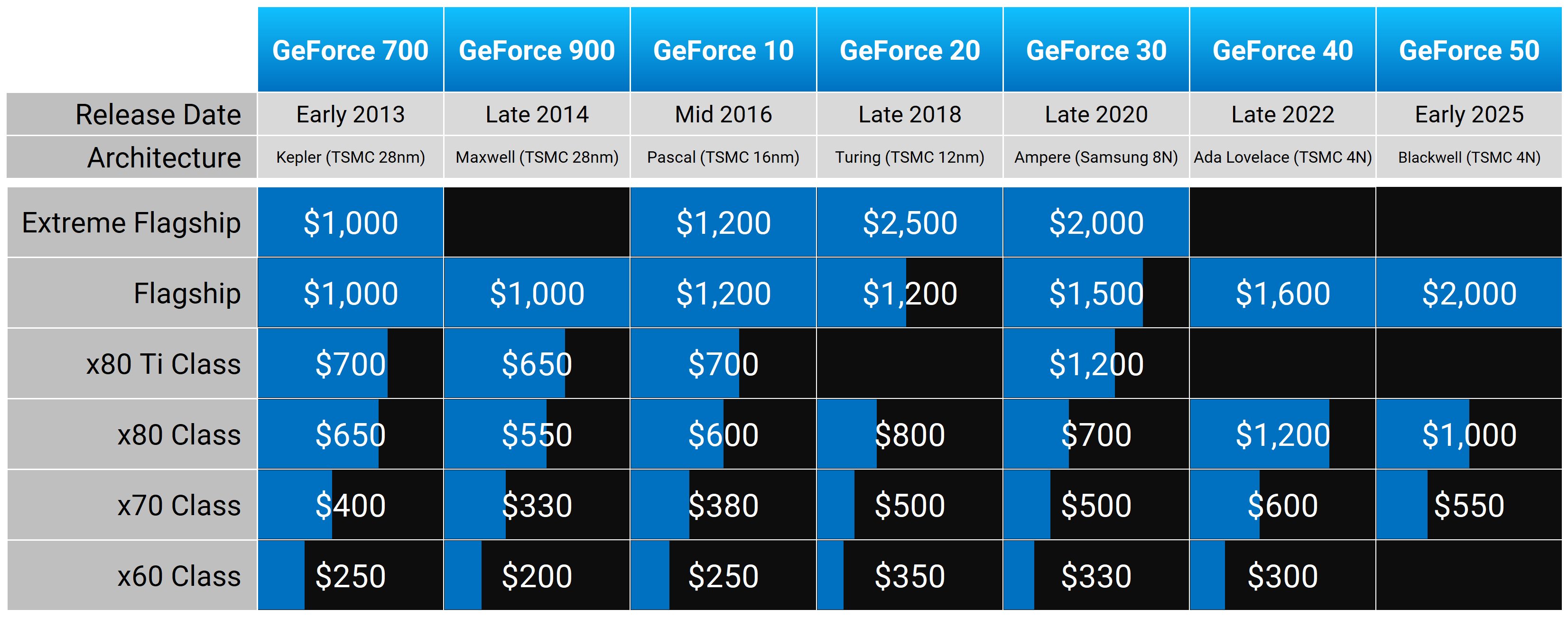

Finally, let’s investigate pricing. Graphics prices have consistently moved upward, with flagship GPUs (historically Titan, currently 90-class) climbing from $1,000 to $2,000 in a decade. This elevation has applied upward pressure throughout the range.

Nvidia GPUs: Launch MSRP Pricing

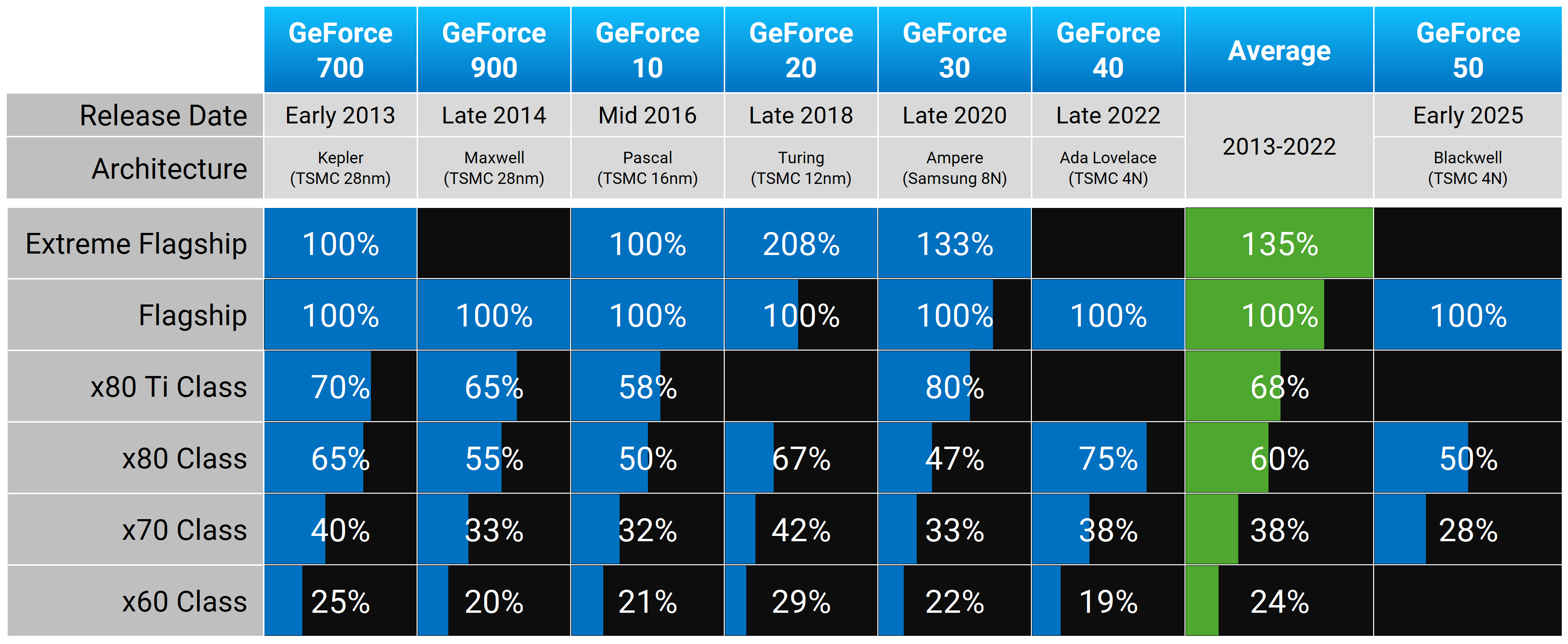

From this viewpoint, Blackwell stands pleasingly against the generational mean from 2013 onward. Typically, an 80-class card is priced at 60% of the flagship; however, the RTX 5080 is at 50%.

While certain generations align, such as the 10 and 30 series, where the 1080 and 3080 hovered around half the cost of the Titan X and 3090 respectively, this is still better than average. If the configurations paralleled what’s expected from an 80-series, a $1,200 price for the 5080 might be fitting, yet with its underwhelming setup, it falls short.

Similarly, pricing for the RTX 5070, while cheaper than historic average pricing for 70-class GPUs, would seem more appropriate at around $750 if the flagship MIG was at $2,000. The relatively favorable pricing only matters if it matched average historical GPU configurations, which regrettably, it doesn’t.

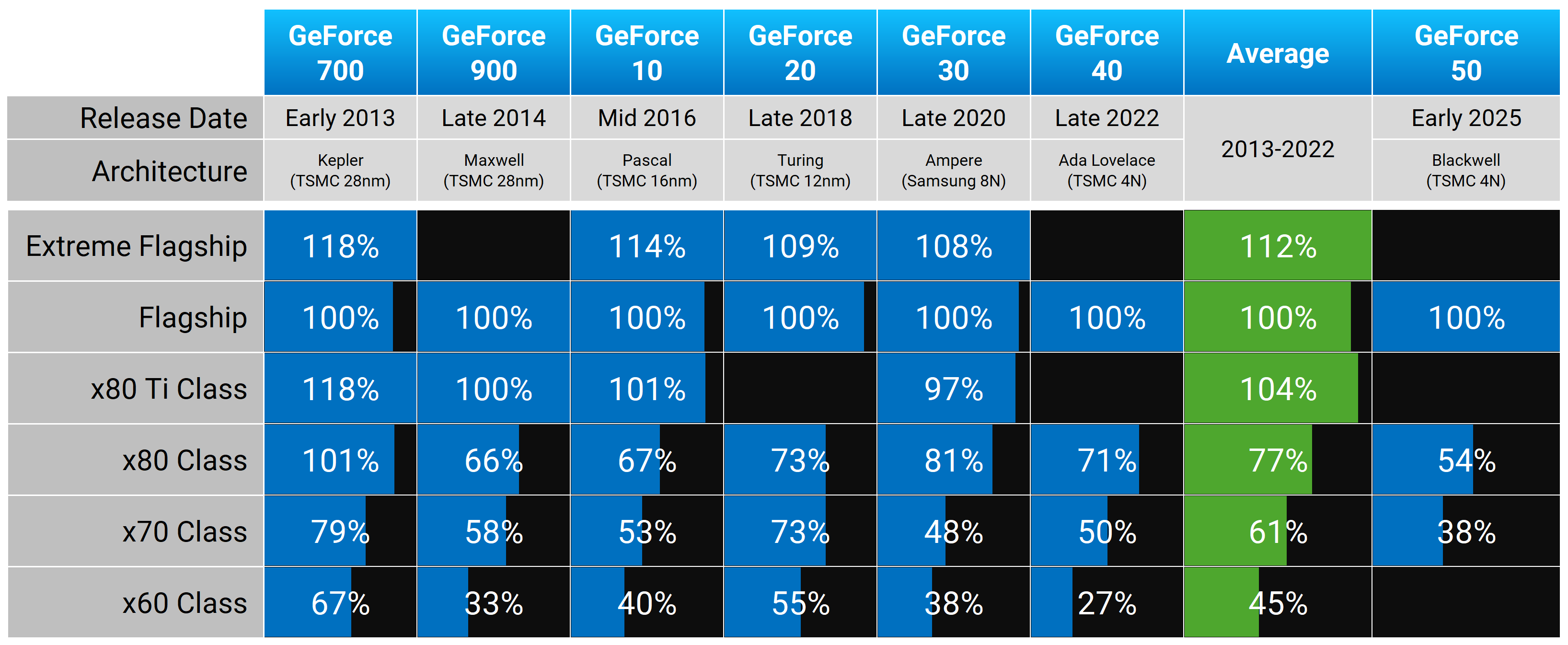

Summation of Nvidia GPU Configurations

This synoptic view of the average six-generation Nvidia GPU configuration highlights the issue perfectly: The GeForce RTX 5080 attributes are analogous to or beneath the stature of a 70-class GPU, yet its price likens more to a median position between the 70 and 80-class tier. Consequently, the RTX 5080 is a subpar 70-class GPU, with Nvidia levying a 70 Ti parallel price.

The RTX 5070 similarly confronts an analogous plight, its hardware under par for traditional 60-class GPUs, likely aligning closer to a notional “50 Ti” model at best, with Nvidia premium pricing it 15% higher than typical 60-class counterparts.

This anomalous pairing between hardware configuration, a key performance driver, and price explains why reviews and apprehensions curated around Blackwell verge on the underwhelming.

Revamping the RTX 5080

Two fundamental approaches could have aligned this generation closer with the GeForce legacy. Firstly, altering configurations would have rendered improvements – for the RTX 5080, enlarging the GPU die lying between GB202 and GB203 would be pivotal. Amplifying shader cores by approximately 47% by escalating from 84 SMs to potentially 124 SMs, summing to 15,872 shader cores, would be desirable.

Boosting memory bandwidth by 43% would easily be achieved by expanding the memory bus from 256-bit to 384-bit, potentially accommodating extra VRAM. This could further validate a price adjustment, setting the 5080 at $1,200 in coordination with historic pricing trends.

With the aforementioned robust design, this re-engineered RTX 5080 could parallel the RTX 4090, albeit $400 cheaper, potentially more when juxtaposed with street pricing of the 4090.

Even then, it mightn’t elicit massive generational advances against models like the RTX 4080 Super, hypothesized at around 35% quicker for 20% costlier alternatives, yet this would pivotably stem from increasing flagship base pricing, invariably escalating the product line.

At a stable $1,000, this aspirational RTX 5080 might be quite alluring, encapsulating RTX 4090 performance permitted at 40-series pricing projections.

This shift would address one of the main challenges the 5070 presently faces, such as its 12GB VRAM constraints. Updating this model to shadow the 80-class band ensures it benefits from at least 16GB VRAM.

For the RTX 5070, aligning with historical 70-class brand trends necessitates a considerably enlarged setup. This configuration could require a larger deployment than the current RTX 5080 overn. However, price support might engage to follow trends observed.

The more direct recourse to address configuration hitches is to lower the existing model and nameplate costs while working presumeably by cost alone.

How About a $700 to $800 RTX 5080?

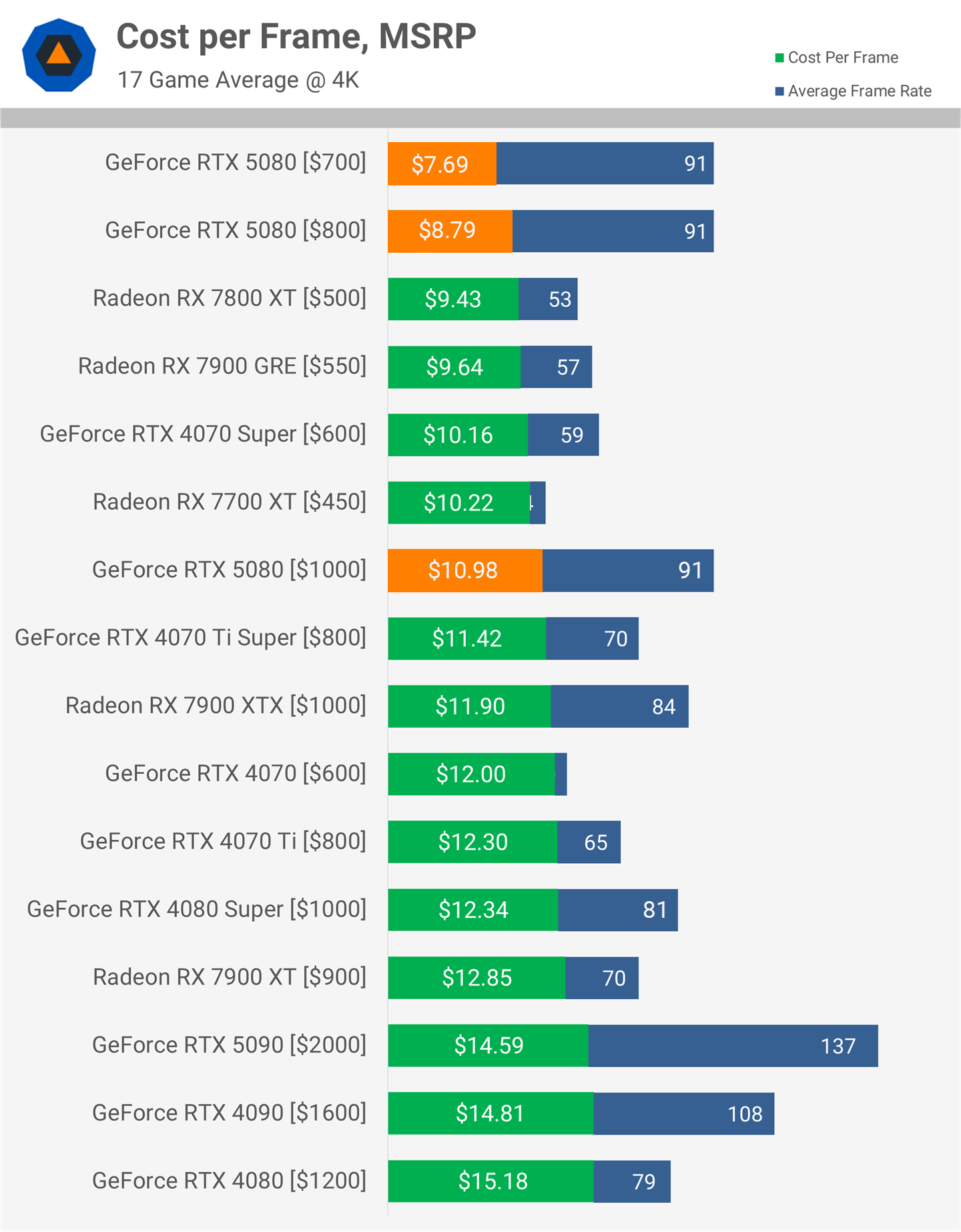

In correlation to the RTX 5080’s current configuration, a price of around 35% of the flagship unit suggests a projection of $700. This translates into a cost per frame of $7.69, amounting to a dramatic 38% reduction compared to the RTX 4080 Super, translating into an enticing generation. Furthermore, this equates with or even slightly curtails the cost per frame upgrade achieved by the RTX 3080 relative to the RTX 2080, one of the finest generational boons until crypto-mining distorted market dynamics.

Perhaps this proposal is overly optimistic given the current GPU market, but setting the figure at $800 seems more aligned considering the hardware configurations in 2025. While expensive historically for a ~70-tier compute block, it nonetheless achieves a 29% reduction per frame compared to the RTX 4080 Super.

Prospects of Enhanced Configuration or Pricing?

The clear counterpoint is the cost spike producing GPUs by 2025. Wafer expenses have surged, memory is pricier, board complexities have risen – overall expenditure has risen.

As configurations and pricing go, the clear caveat here is the rising expense of producing a GPU in 2025 versus previous times, especially comparing back to GeForce 900 or 10 series era. Wafer costs are significantly elevated, memory costlier, board compositions more sophisticated – almost every element bears a larger cost. Furthermore, ordinary inflation over a decade adds to the balance of undertakings.

Nvidia chiefly utilises this as a response when high pricing is questioned when it comes to GPU costs over the years. The critical inquiry is whether it’s thus justified for hardware previously categorized as 70-class to realign to an 80-class pricing tier come 2025.

Firstly, let’s scrutinize die dimensions. Across the years, there has been some variability concerning GPU silicon quantities amongst products and refine models, albeit the general modus operandi has stayed unchanged. The RTX 5070 die, GB205, ranks amongst the smallest in the past seven 70-class generations. Meanwhile, GB203 on the RTX 5080 surpasses the 80-class average, despite hovering above the 70-class mean figure.

Nvidia GPUs: Die Size (sq. mm)

The dilemma Nvidia faces is the steep rise in TSMC wafer prices. Nursing 378 sq mm of 4N silicon enacts a notably higher cost than preparing 398 sq mm of 28nm silicon experienced in the GeForce 900’s production. However, does this extensively account for the GTX 980 debuting at $550, GTX 1080 at $600, now RTX 5080 balloons to $1,000?

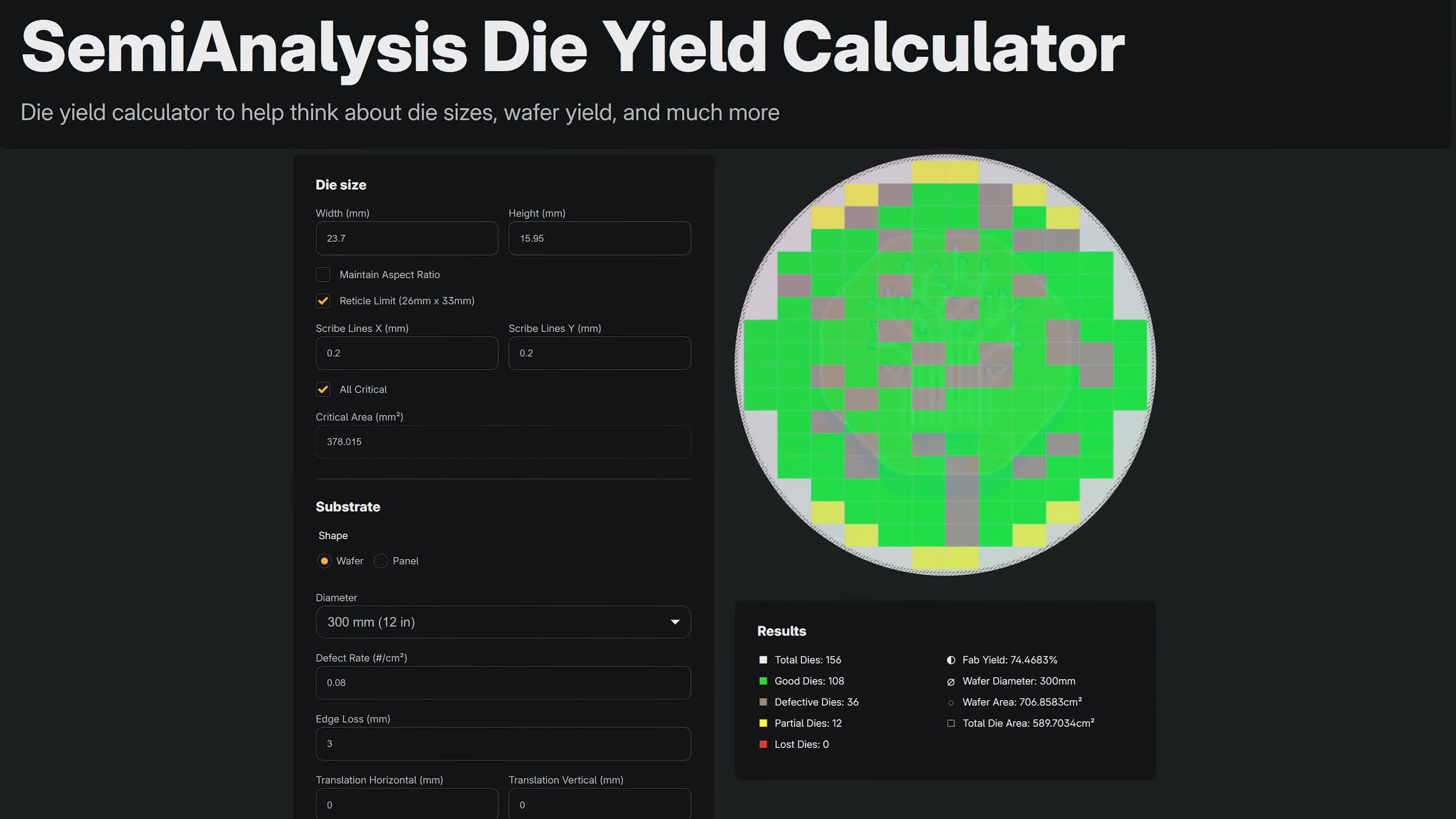

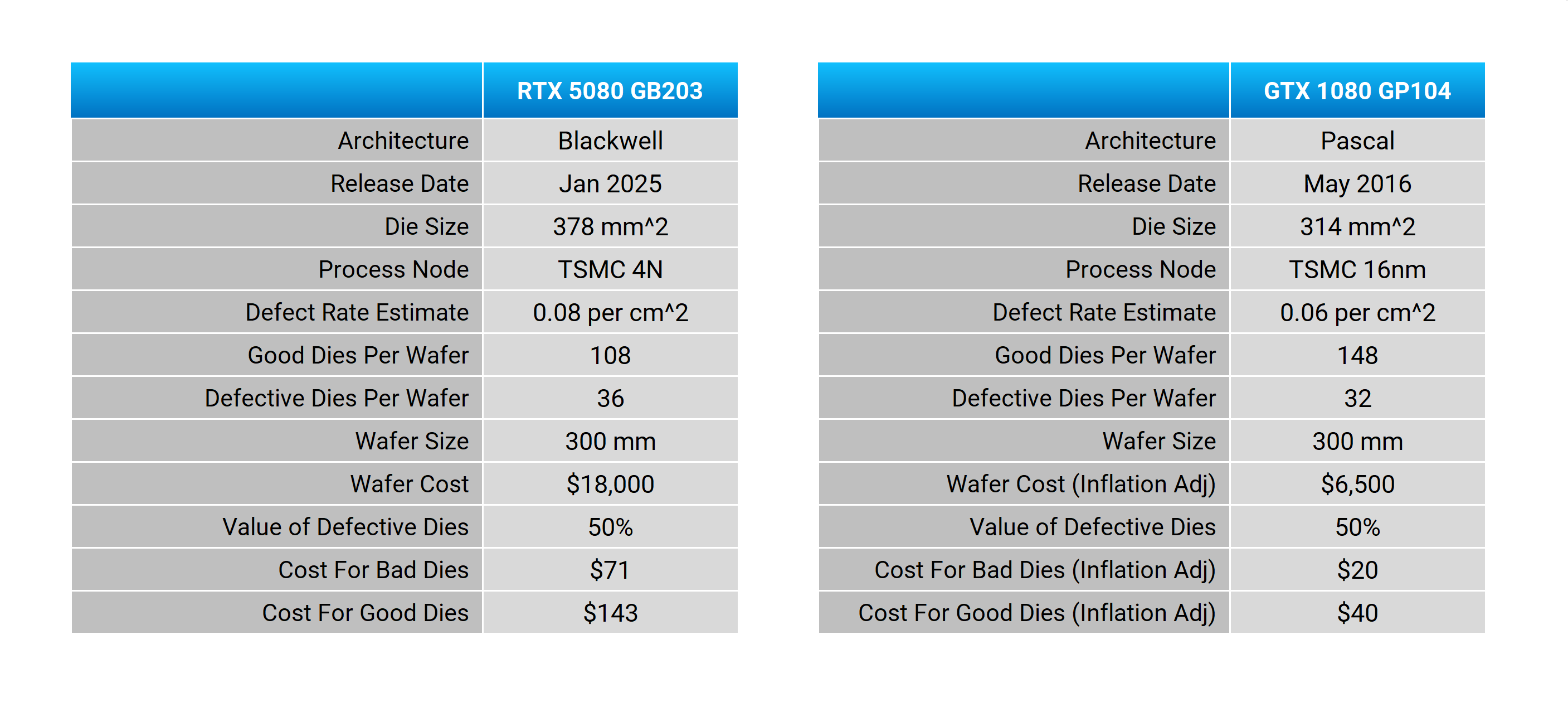

After conducting calculations using rough die size estimates, yields – integrated with SemiAnalysis Die Yield Calculator – along with conjectured TSMC wafer costs, we presumed defective die relative to market-quality die values, positing good die requirements per product basis.

Per this model, GB203 dies for the RTX 5080 came up as costing approximately $140. Let’s clarify, it’s a rough estimate, not a precise cost. Besides, it’s not the exclusive constituent of the RTX 5080. The memory, PCB, cooler, silicon packaging, and developmental expense also hover in the cost equation.

Nvidia GPUs: Die Cost Rough Estimate

We replicated this process for GP104 silicon historically instrumental in the GTX 1080 GTX 1070, utilizing TSMC’s 16nm fabrication and adapted inflation measures.

Our quick estimation for GP104-rated die was $40. Consequently, between Pascal till the present, 70-class silicon expenditure has risen from $40 to $140, merging in a $100 increase or 3.5-fold cost surge.

This might emerge from the higher boundary based on input variables, yet, even with more favorable biases for TSMC 4N silicon costs, an increase beyond 2.5 fold seems unfaltering.

Inflation vs. Hardware Cost vs. Competitiveness

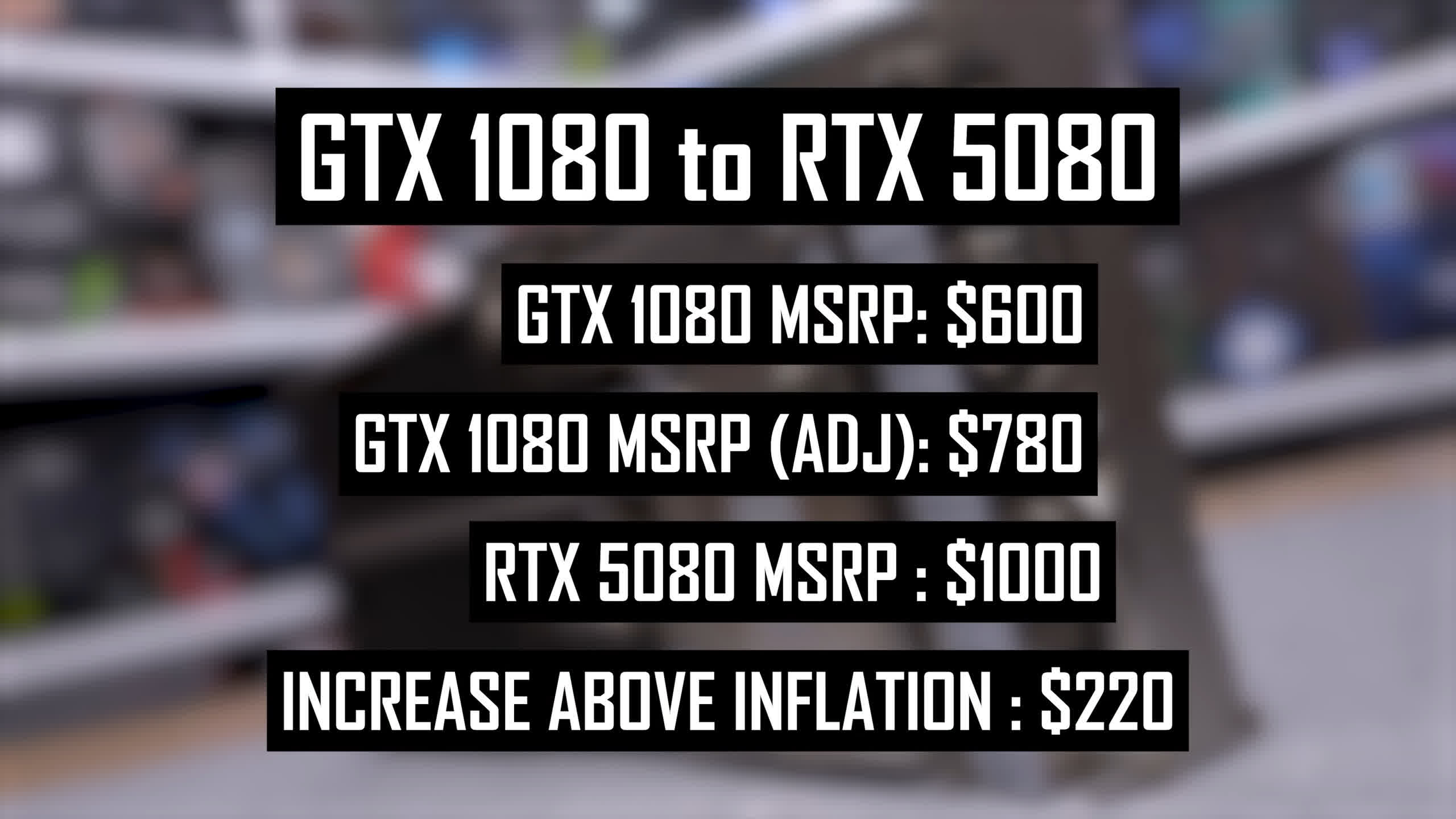

Nvidia’s GeForce GTX 1080 debuted at $600 in 2016, whereas the GTX 1070 was unveiled at $380. Accounting for inflation, present valuation marks $780 and $500 respectively. Accounting for approx $100 added GPU silicon costs, plus the shift from 8GB GDDR5-class memory to 16GB GDDR7, alongside increased cooler demands for 360 watts against 180 watts plus power stages to calibrate both models.

Price hikes exemplified Nvidia puts the full die model – e.g., GTX 1080 ups to RTX 5080 – $220 above inflation. Meanwhile, for the trimmed model – GTX 1070 vis-à-vis the RTX 5070 Ti – the differential lies $250 higher in perception, neglecting the trimmed configurations relative to the flagship graphs.