The evolution of photography has been underway for centuries, with the first film cameras emerging in the 1800s. However, the underlying principles of photography have been known for millennia, dating back to at least the 5th Century BC when the Chinese philosopher Mozi documented the concept for the first time.

Advertisement

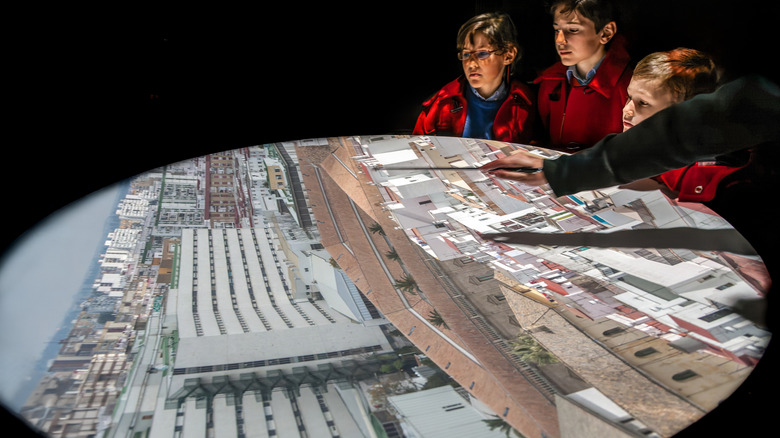

Although photo film didn’t exist over two thousand years ago, the concept of using a “camera obscura” enabled some individuals to understand light and reflections enough to view and record images. The device was primarily utilized as a basic projector to render a scene’s image or subject onto a sheet of paper, where an artist could trace it.

Modern cameras may not have a tiny person inside crafting swift and detailed drawings, but many foundational ideas have endured through time.

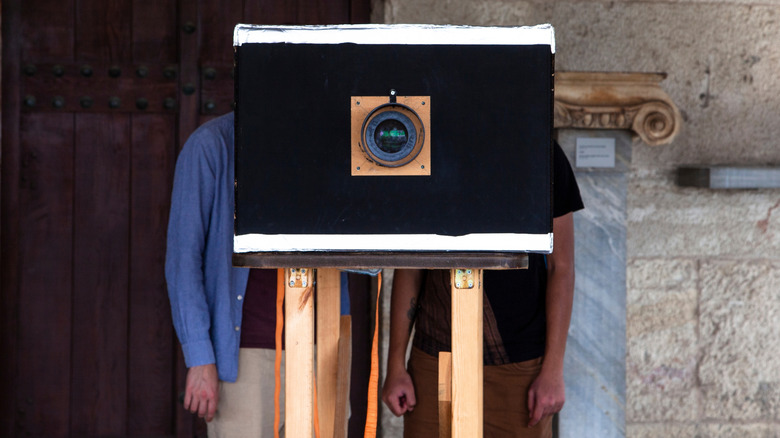

What counts as a camera obscura?

The term camera obscura translates from Latin to “dark chamber,” suggesting that any dark room or container could be classified as a camera obscura. However, a functioning camera obscura requires more than just darkness; it also necessitates a small opening on one side to permit light entry.

Advertisement

This small light entry is what significantly affects the projection, as it causes the scene in the illuminated area to cast an inverted image on the interior wall of the camera obscura. The clarity of the image improves with a white surface, although it isn’t strictly necessary.

Interestingly, just about any instance where bright light filters through a narrow opening into a larger space can create this optical illusion. You may have experienced this phenomenon when observing an upside-down, hazy image of the outdoors projected onto a wall by partially open blinds. This is essentially another example of a camera obscura!

Advertisement

But how, though?

What’s fascinating is that images are perpetually projected and reflected off every surface that isn’t in complete darkness; the issue is those reflections often appear out of focus and muddled together. By metaphorically narrowing the light through a small opening, the resulting images can be brought into sharper focus.

Advertisement

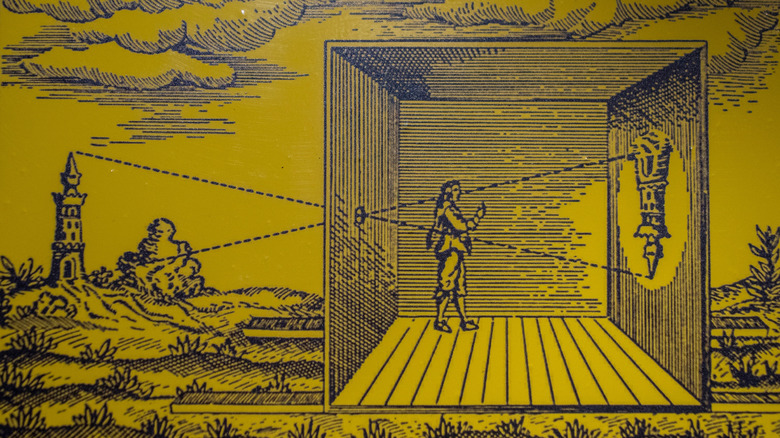

In a more intricate explanation, nearly all objects reflect light, dispersing those reflections in numerous directions. By having a surface (like a wall or the interior of a box) face a lit object and minimizing the size of the opening that permits light to reach that surface (similar to the concept of a photography aperture), other reflections that don’t travel straight on can be blocked out. Thus, the reflections that manage to get through yield an image of the object. A narrower opening results in reduced visual noise and provides a clearer reflection.

Moreover, the image appears flipped upside down because light travels in straight lines. As light bounces off the top of an object at a downward angle, it passes through the opening and ends up at the bottom of the receiving surface, which is why illustrations of these principles typically feature cone-shaped representations for light.

Advertisement